Hace no mucho tiempo, hacia finales del siglo II a.C. y principios del siglo I a.C., los habitantes de Magdala comenzaron a mostrar que eran una sociedad bien organizada, tanto en lo político como en lo administrativo. Su arquitectura y urbanismo son testimonio de ello, con un puerto bien estructurado que facilitaba las actividades de pesca, almacenamiento y transporte. Los edificios de la ciudad, como la sinagoga o los espacios rituales, contaban con un sistema constructivo e ingenieril eficaz para evitar inundaciones durante la temporada de lluvias. Todo esto fue posible gracias a una economía que dependía de diversas actividades comerciales, industriales y agrícolas, actividades que fueron creciendo con el tiempo. Así, Magdala, también conocida como Taricheae en griego, se convirtió en una de las ciudades más prósperas a orillas del lago de Galilea, un lugar tan significativo que el lago llegó a ser conocido como el Mar de Taricheae por algunos habitantes y viajeros, según los relatos de Plinio el Viejo (Plin. Nat. 5.71).1

Con el desarrollo de las ciudades y pueblos en Galilea, el uso de monedas se volvió cada vez más común e importante para facilitar el comercio entre ciudades, el pago de servicios, impuestos, materiales, y más. Esto no es muy distinto de lo que hacemos hoy en día al pagar peajes en las carreteras cuando vamos de una región a otra. Las monedas se convirtieron en una parte esencial de la economía, el comercio y la política de la región, representando no solo el dinero en las transacciones, sino también el control político de la época.

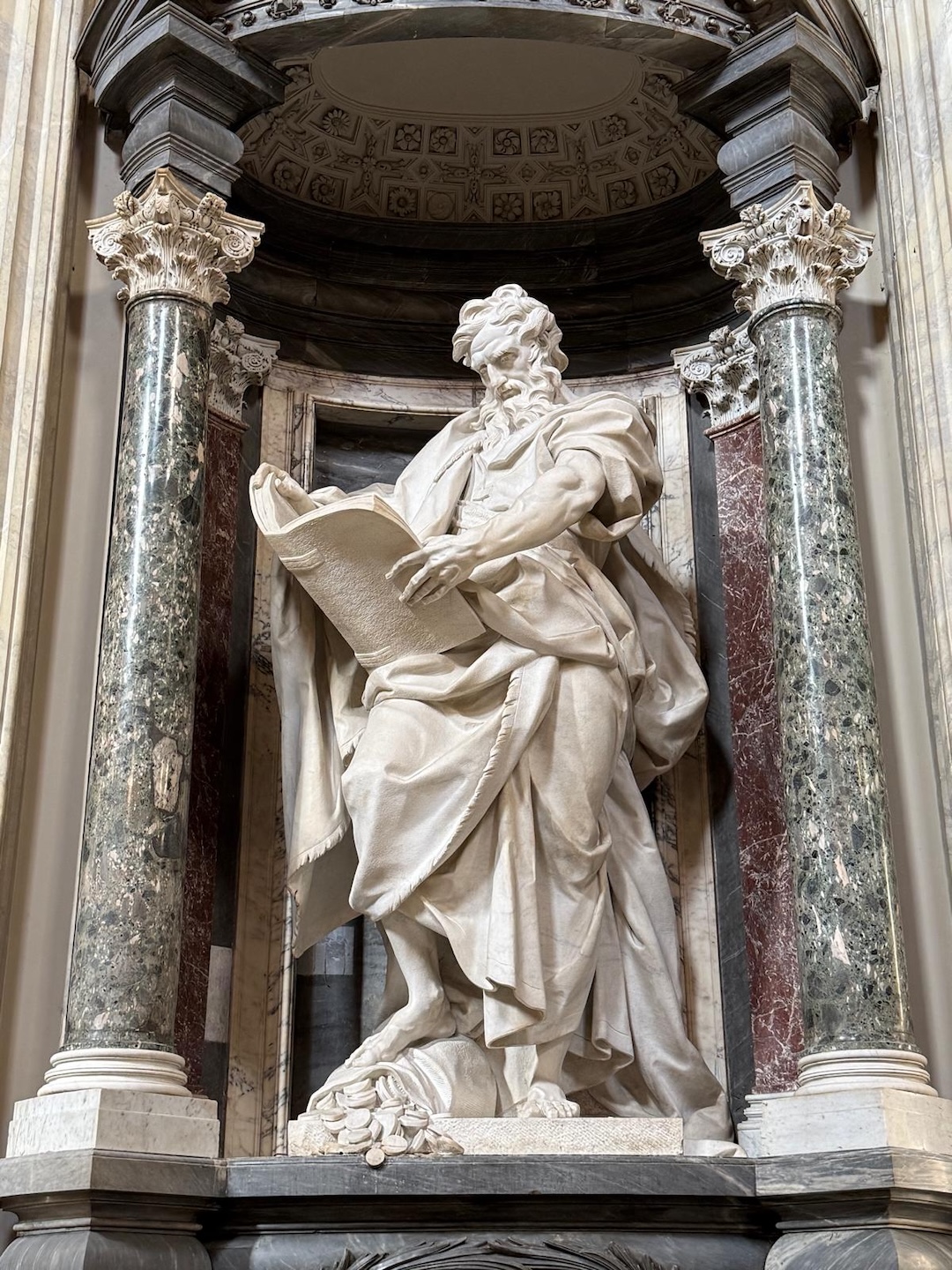

Las monedas que circularon por las calles de Magdala durante el siglo I, en la época en que Jesús y sus apóstoles recorrían Galilea a pie y en barcas, eran principalmente monedas judías de bronce acuñadas en Jerusalén y Tiberias.

Entre ellas se encuentran las acuñadas bajo el reinado de Alejandro Janneo, un rey Hasmoneo que, aunque falleció en el año 76 a.C., dejó monedas que continuaron en circulación por aproximadamente 100 años más. También circulaban monedas de Herodes el Grande, de Agripa, Poncio Pilato y de Antipas, estas últimas acuñadas en Tiberias. Con el paso de los años los gobiernos fueron cambiando y así también las monedas.

En conclusión, Magdala se destacó como una ciudad vibrante y bien organizada a orillas del lago de Galilea, desde finales del período helenístico hasta finales del período romano. Su desarrollo urbano y económico, impulsado por un puerto que favorecía la pesca y el comercio, demuestra cómo sus habitantes supieron aprovechar al máximo su entorno, además de otras actividades. Las monedas que circulaban por sus calles no solo facilitaban las transacciones diarias, sino que también reflejaban el poder político de la época. Todo esto convirtió a Magdala en un lugar próspero y lleno de vida, donde la historia dejó una huella importante que aún podemos descubrir a través de su arqueología.

Not too long ago, towards the end of the 2nd century BC and the beginning of the 1st century BC, the inhabitants of Magdala began to show that they were a well-organized society, both politically and administratively. Their architecture and urban planning stand as evidence of this, with a well-structured port facilitating fishing, storage, and transportation activities. The city's buildings, such as the synagogue and ritual spaces, featured an effective construction and engineering system designed to prevent flooding during the rainy season. All of this was possible due to an economy that relied on various commercial, industrial, and agricultural activities, which grew over time. Thus, Magdala, also known as Taricheae in Greek, became one of the most prosperous cities on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, a place so significant that the lake came to be known as the Sea of Taricheae by some locals and travelers, according to the accounts of Pliny the Elder (Plin. Nat. 5.71).

With the development of cities and towns in Galilee, using coins became increasingly common and important for facilitating trade between cities, paying for services, taxes, materials, and more. This is not different from how we pay highway tolls when traveling from one region to another today. Coins became an essential part of the region's economy, trade, and politics, representing not only money in transactions but also the political control of the time.

The coins circulating through the streets of Magdala during the 1st century, when Jesus and his apostles traveled through Galilee on foot and by boat, were primarily Jewish bronze coins minted in Jerusalem and Tiberias.

Among them were those minted under the reign of Alexander Jannaeus, a Hasmonean king who, although he died in 76 BCE, left coins circulating for about 100 years more. Coins from Herod the Great, Agrippa, Pontius Pilate, and Antipas, the later minted in Tiberias, were also in circulation. Over the years, as governments changed, so did the coins.

In conclusion, Magdala stood out as a vibrant and well-organized city on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, from the end of the Hellenistic period to the end of the Roman period. Its urban and economic development, driven by a port that favored fishing and trade, demonstrates how its inhabitants made the most of their environment and other activities. The coins that circulated through its streets facilitated daily transactions an reflected the political power of the time. All this made Magdala a prosperous and lively place, where history left an important mark that we can still discover through its archaeology.

Descubre más artículos de esa categoría